Neural networks are transforming AI and will impact our society in ways we can’t begin to imagine. The possibilities are endless: from autonomous vehicles to revolutionizing healthcare. The hardware industry is clearly excited about this revolution, as can be seen from the number of AI hardware startups and huge investments from the semiconductor giants. A recent blog on xPU for AI acceleration provides a good list of many accelerators including industry projects.

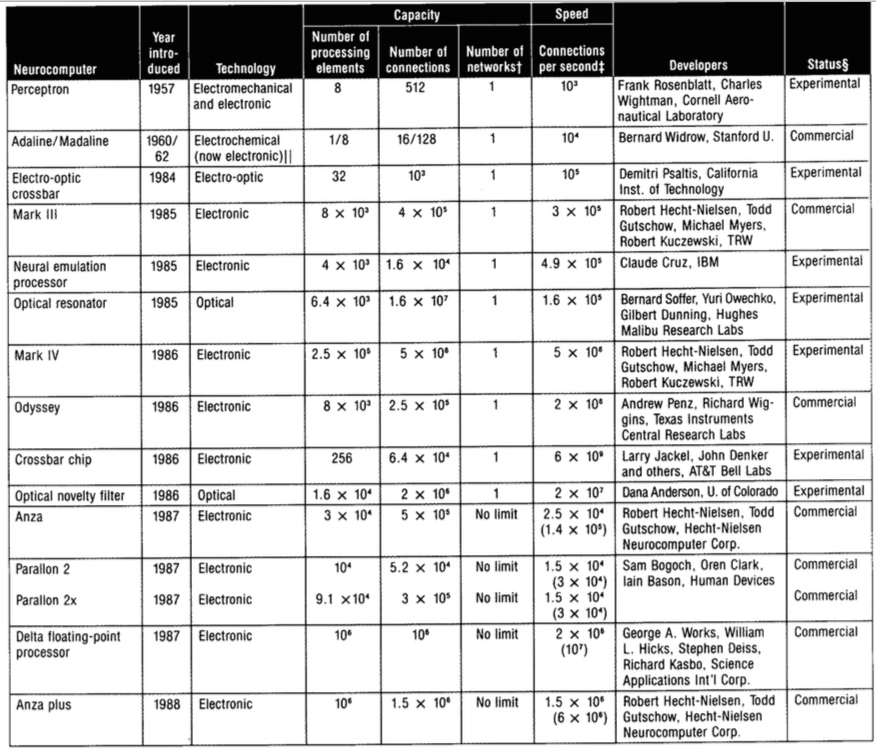

However, this blog article is not about today – it is about yesterday – it is a throwback to 90s neural chips. Much like today, there was a significant buzz around neural networks in the late 80s and 90s. The target applications were a subset of today: language translation, speech and image recognition, and automobile autopilot. And the interest was not only academic. Several corporations in US, Europe and Japan had developed a plethora of commercially available Neurochips. Here is a table of Neurochips from Robert Heicht-Neilson’s 1988 article.

And the table had missed several platforms that are worth checking out: NETSIM (Texas Instruments and Cambridge University, UK), SYNAPSE-1 (Siemens AG, Corp, R&D, Germany), CNAPS (Adaptive Solutions, Inc., USA), SNAP (HNC, CA, USA), LNeuro 1.0 (Neuromimetic Chip, Philips, Paris, France), Mantra I (Swiss Federal Institute of Technology), ZISC036 (IBM Microelectronics, France), ETANN (Intel Inc., CA, USA), SAIC SIGMA-1 (Science Applications International Corporation), NT6000 (Neural Technologies Limited, HNC, and California Scientific Software), Balboa 860 (HNC, CA, USA), Ni1000 Recognition Accelerator Hardware (Intel Corp), NBS (Micro Devices, FL, USA), Neuro Turbo I&II (Nagoya Institute of Technology, Mitec Corp., Japan), WISARD (Imperial College London, UK), Topsi (Texas Instruments, USA), DREAM Machine (Hughes Research Laboratories, CA, USA).

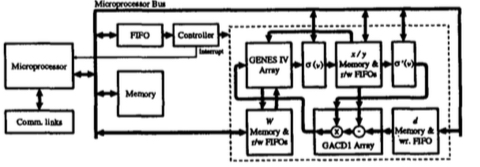

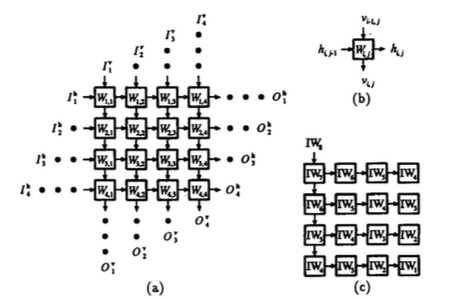

Let us take a closer look at one of these machines: MANTRA I by Swiss Federal Institute of Technology. MANTRA I was a 2D array of up to 40×40 GENES IV systolic processors and a few auxiliary processors. The GENES chip (Generic Element for Neuro-Emulator Systolic arrays) consisted of bit-serial processing elements that performed matrix operations. Today neural accelerators share similar architectural features: systolic arrays and configurable precision.

The general architecture of MANTRA I machine

(a) GENES IV systolic array architecture (b) Definition of input/output path of PE (c) Systolic flow of instruction words

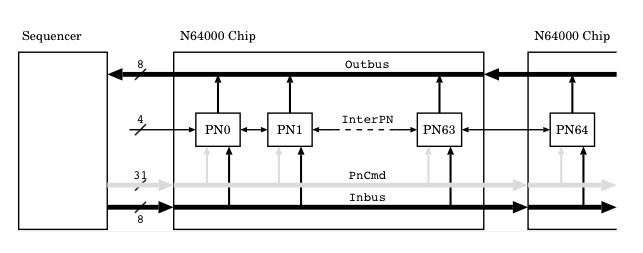

SIMD processing was also quite popular in the older systems. CNAPS neuro-computer had several N6400 chips. Each chip had a SIMD array with 64 processing elements. A common sequencer broadcasted commands to all chips.

CNAPS. Interchip contribution.

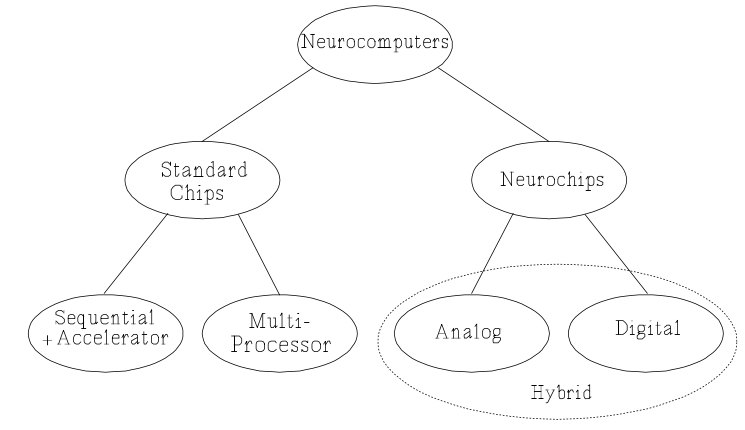

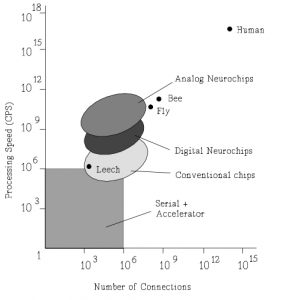

Interestingly, like today, researchers then had also developed digital, analog and hybrid neuro-accelerators. Analog computing provided higher performance, but its precision was a concern then and is a concern now as well. See this taxonomy picture and a relative throughput of these systems taken from Heemskerk’s 1995 survey.

Yesteryear neurochip architects paid significant attention to the network that connected the processing elements. Regular 2D, 3D, ring-based topologies were explored. I have not seen much attention being paid to the network architecture of modern DNN accelerators. Perhaps board-level integration made network critical then.

Old Neurochips did not seem to have multi-threading. GPUs, which are one of the most popular neural accelerators today, employ massive multi-threading. This feature is perhaps necessary today as many modern DNN models are much larger in size and it is important to hide memory latency.

Research in 1990s even investigated optical neural networks. For instance, BPD Corp produced optical neurocomputer which had LED arrays for sending output signals and arrays of phototransistors for receiving weighted input signals. Other optical neurocomputers from CALTECH, Hughes Research Labs, Mitsubishi, and Tokyo University used holographic associative memory based architectures. It will be cool to revisit these optical neurocomputers given the advancements in photonic technology.

Parting Thoughts. AI and AI accelerators have experienced a staggering growth in the last few years. As we continue this journey, it is worthwhile to understand the historical context.

About the Author

Reetuparna Das is an assistant professor in the University of Michigan. Feel free to contact her at reetudas@umich.edu

Disclaimer: These posts are written by individual contributors to share their thoughts on the Computer Architecture Today blog for the benefit of the community. Any views or opinions represented in this blog are personal, belong solely to the blog author and do not represent those of ACM SIGARCH or its parent organization, ACM.