“It’s not that easy bein’ green.” – Kermit the Frog, 1976

We likely just published the first paper to report the carbon footprint of manufacturing AI accelerators. This life-cycle assessment in a real-world setting found that hardware operation emits more CO2 than manufacturing: “Operational emissions dominate AI hardware lifetime at 70% to 90% of total emissions… .” That’s good news, as reducing manufacturing CO2 is more challenging since it requires coordinated efforts across the supply chain; >100 vendors supply components for Google’s AI servers. However, based on environmental reports from Facebook and Google, a 2021 HPCA paper concluded that for all cloud companies “most emissions are capex-related—for example, construction, infrastructure, and hardware manufacturing.”

Both papers rely on standard environmental practices; why do they disagree?

To answer this question, let me first retrace my exploration of the environmental landscape. We’ll see a few accounting differences, importantly the carbon footprint equivalent of a movie set facade—those fake buildings in Hollywood films. They’re impressive from the front, but from behind they’re just wooden supports and empty space.

Hollywood movie facade from the front and from the back

Here is a quick language guide you’ll need on our tour:

- GHG or Greenhouse Gasses include CO2, methane, nitrous oxide, and a few more.

- CO2e or carbon dioxide equivalent emissions, measured in kilograms, account for the other GHG.

- Embodied CO2e refers to manufacturing emissions plus transportation emissions.

- Operational CO2e comes from operating the hardware, mostly from electricity consumption.

- GHGP or Greenhouse Gas Protocol in 2004 set the rules for accounting of emissions: who should be responsible for what in a supply chain, what to include and exclude, how to verify claims, and so on.

- Environmental Reports (ERs) are annual company filings documenting its CO2e per GHGP rules.

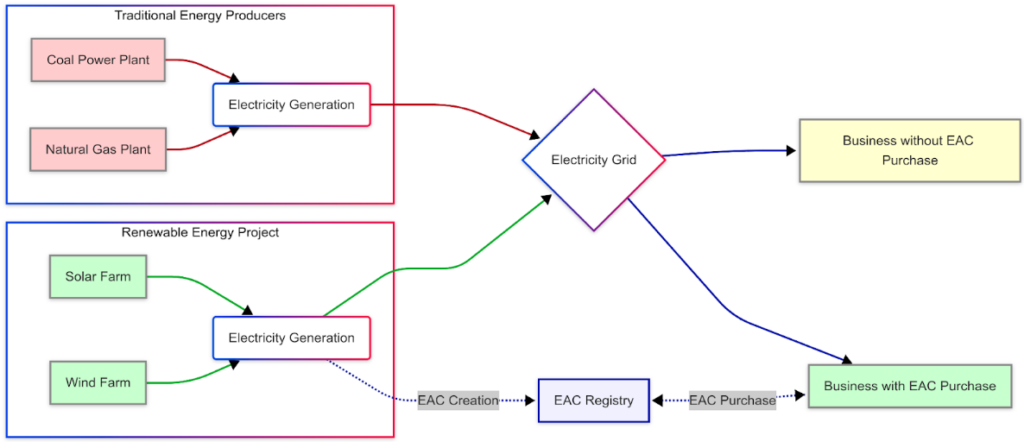

- EACs or Energy Attribute Certificates are GHGP instruments that specify the Carbon Free Energy (CFE) emissions rating of the purchased energy source (i.e., clean energy, see Figure 1).

- Bundled EACs are EACs purchased together with renewable based electricity.

- Unbundled EACs mean purchasing only the certificates but not the renewable energy.

Figure 1. Each MWh of renewable energy produced creates one EAC in the registry. Businesses buying that energy get “bundled” EACs via the registry. GHGP also allows far away businesses to buy only the “unbundled” EACs from the registry to get credits to be used sometime that year to offset CO2e from energy bought from traditional energy producers.

To calculate operational electricity-related emissions, we multiply operational electricity consumption by the annual average electricity emission factor, which varies by location. For example, electricity emissions in coal-powered West Virginia are ~10X worse than hydroelectric-powered Seattle (840 vs 80 kgCO2e/mWh) and in Europe, for similar reasons, Bełchatów, Poland emissions are ~75X higher than Oslo, Norway (760 vs 10).

The two commonly accepted GHGP emissions accounting methods are:

- Location-based (LB) refers to the GHG emissions emitted within a specific geographic boundary, such as a country or grid region. LB emissions are calculated using the annual average electricity emissions factor for the defined grid. They exclude the impact of CFE procurement, so it’s conservative.

- Market-based (MB) GHG emissions account for the GHG emissions emitted by generating sources from which a company purchases electricity and associated EACs. Unlike LB, it credits companies for CFE purchases, allowing them to reduce their associated MB emissions.

It is important that companies have market-based options to reduce their emissions through CFE purchases.

The value of the EAC market in 2023 was $10B, projected to grow to $100B by 2030. The problem, however, is that few companies actually align their CFE purchases with where and when they consume electricity. The GHG Protocol Scope 2 Guidance—announced a decade later—allows companies to procure CFE to match their annual electricity demand, often far from where they consume power (same continent). Moreover, many companies rely on unbundled EACs to reduce their emissions, which often do not lead to actual emissions reductions, in contrast to more direct purchasing methods like long-term power purchase agreements using bundled EACs. In fact, unbundled EACs were the largest source of green power in 2022, but their share is declining for reasons we shall see.

Are unbundled EACs really green?

Unbundled EACs have come under criticism for being misleading. They reduce emitted CO2e negligibly—the majority of the companies’ energy use was still fossil fuels—and moreover are not likely to lead to greater investments in clean energy development beyond what was already planned. Since unbundled EACs are available inexpensively anywhere on the same continent anytime of the year, local utilities are not motivated to invest in CFE.

How much do hyperscalers that house numerous AI accelerators rely on unbundled EACs? The table below pairs unbundled EAC percentages in 2023 as reported by the Financial Times with LB and MB emissions from the companies’ environmental reports. The first four companies claim to offset 82%, 95%, 100%, and 100% of their LB emissions using MB accounting. How well these companies really reduce CO2e is left to the reader. (Late breaking news: as I finished this paper, Microsoft announced it is going to stop purchasing unbundled EACs in the future.)

| Company | % unbundled EACs of total energy | LB-based GHG emissions (billion kgs CO2e) |

MB-based GHG emissions (billion kgs CO2e) |

| Amazon | 58% | 15.7 | 2.8 |

| Microsoft | 53% | 8.1 | 0.4 |

| Apple | 9% | 1.2 | 0.003 |

| 6% | 5.1 | 0.002 | |

| 0% | 9.3 | 3.4 |

Clearly, the use of unbundled EACs can lead to very different conclusions for what actions to take. They are allowed under the current GHGP standard, but many think that they can be misleading when considering real reduction opportunities. The GHGP standards need to be improved so that the whole system can be better aligned with decarbonization in reality versus a decarbonization facade.

Besides unbundled EACs, another major reason for the dispute about the importance of operational versus embodied for cloud companies is that the HPCA paper tried extrapolating embodied CO2e from environmental reports (ERs), as they didn’t have life-cycle assessments (LCAs). Our paper explains the differences; basically, LCAs amortize embodied CO2e over the equipment lifetimes but ERs typically don’t, and ERs include equipment outside the data center like office buildings and end-consumer devices. LCAs are the most accurate way to assess embodied emissions. Also, we focus on AI accelerators and their CPU hosts that dominate cloud purchases but they include storage servers and general purpose servers.

A better way to account for AI emissions

To reduce CO2e in a way that’s focused on grid decarbonization, we believe that it’s important to purchase CFE that meets demand where and when it occurs. That motivated Google’s goal of 24/7 Carbon-free Energy. It expands the traditional GHGP rules to restrict both the location and time period where CFE purchases can be applied to reduce emissions.The 24/7 Carbon- free Energy Compact launched by Sustainable Energy for All and UN-Energy—signed by 160 companies, governments, and organizations—helps organizations achieve this goal. Because of the credibility issues in the public over questionable GHGP-allowed practices, the GHGP guidance is being revised. One option is requiring more granular (hourly and local) accounting for market-based emissions, similar to 24/7 CFE. (Slide 7 from a recent GHGP working group meeting shows it performing best in a poll on five options.)

Using 24/7 CFE, a megaWatt-hour (MWh) of purchased CFE must be matched to a MWh of consumed electricity that is delivered to the same local grid boundary—in the continental US, one of the 66 balancing authorities—and in the same hour where consumption occurs. Thus, like LB accounting, 24/7 is restricted in time and space but unlike LB it includes CFE purchases. This more accurate accounting disallows CFE purchases made from different geographies not matched with hourly consumption from reducing electricity emissions; if Google cannot get 100% CFE from the local grid plus its clean energy contracts in any hour, the shortfall counts against the goal. Thus, the 24/7 emissions metric is larger than MB emissions, yet it still reflects emissions reductions unlike the conservative LB metric. For example, Google’s 2023 emissions factor under 24/7 CFE would be 212 kgCO2e/mWh versus 135 kg using standard MB accounting and 366 kg using LB accounting.

Besides more accurately accounting for a company’s carbon emissions, several academic studies find that local and hourly matching of CFE accelerates decarbonization of the broader electricity system, including by accelerating the commercialization of advanced CFE technologies. For these reasons, we recommend that the AI community adopt these more accurate and impactful accounting standards for addressing its emissions.

What about operational emissions in the future?

Our paper also speculates about a rosier future day where 90% of energy use by data centers is CFE, and then even rosier if 90% of the energy for manufacturing was also CFE. In both futuristic scenarios, operational CO2e would still be significant, at ~40%–50% of total emissions.

Conclusion

In summary, the three reasons for the conflicting claims about operational versus embodied importance are:

- Different operational CO2e accounting. Most hyperscalers use unbundled EACs to claim reduced operational emissions, but Google does not.

- Different embodied CO2e accounting. LCAs amortize embodied CO2e over a hardware’s lifetime, reducing its value, while ERs do not. ERs are easier to use but are much less accurate than LCAs.

- Different server mix. A smaller point is that our paper focuses on AI servers—the main focus of data center investment today—while their paper includes storage and general purpose servers, whose lower power versus AI chips leads to lower operational CO2e.

Having completed our tour of the GHGP landscape, I hope you’ll agree that:

- From a hardware designer’s perspective, optimizing operational energy efficiency is the single best way to reduce lifetime CO2e for the AI machines we design.

- From a data center designer’s perspective, locating them in regions with low carbon electrical energy has the largest single benefit.

- “Energy is physics, but emissions is accounting,” as a colleague advised me at the start of my journey.

- We’d more likely reduce CO2e and fairly compare results if more companies were not seduced by the permissive GHGP market-based accounting and instead embraced accounting more like the prudent 24/7 CFE.

Acknowledgements

I thank my co-authors (Ian Schneider, Hui Xu, Stephan Benecke, Keguo Huang, Parthasarathy Ranganathan, and Cooper Elsworth) for their work on which this blog is based (Section 4.2 and Appendix C); Samira Khan for suggesting I write it; and Stephan Benecke, David Brooks, Jeff Dean, Cooper Elsworth, Keguo Huang, Samira Khan, Xiaoyu Ma, Jennifer Switzer, Devon Swezey, Hui Xu, and Cliff Young for their helpful comments.

About the Author

David Patterson is a UC Berkeley Pardee professor emeritus and a Google distinguished engineer. His most influential Berkeley projects likely were RISC and RAID. His best-known book is Computer Architecture: A Quantitative Approach. He and his co-author John Hennessy shared the 2017 ACM A.M Turing Award and the 2022 NAE Charles Stark Draper Prize for Engineering. (The Turing Award is often referred to as the “Nobel Prize of Computing” and the Draper Prize is considered a “Nobel Prize of Engineering.”) He recently shared his life lessons from the first half century of his career.

Disclaimer: These posts are written by individual contributors to share their thoughts on the Computer Architecture Today blog for the benefit of the community. Any views or opinions represented in this blog are personal, belong solely to the blog author and do not represent those of ACM SIGARCH or its parent organization, ACM.