In academia, your teachers/advisor lays out well defined goals: Get an A in the class to prove your knowledge of the material; Publish in top tier conferences or journals to prove your research capabilities. Finish all the required classes and/or publish the requisite number of conference papers and write your thesis, and you will graduate. There are relatively objective standards by which your work is judged, and students understand what is required to succeed in school.

Most graduates with degrees in a technical field will work in industry, even those with PhDs. So what are the metrics by which one is measured in industry? How does one “succeed” and what exactly is success anyway? In this article, I’ll discuss some thoughts on this subject colored by my own experience and knowledge gleaned from twenty plus years in industry.

Grades Aren’t Everything

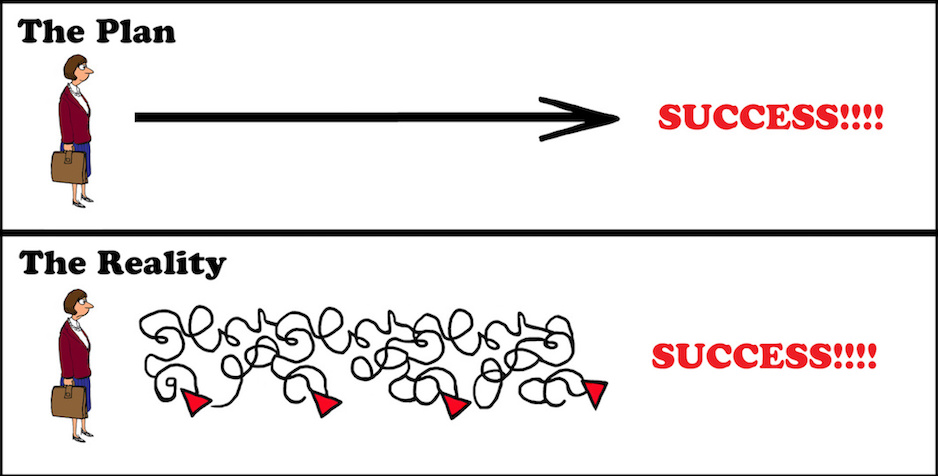

In the article by Simard and Gilmartin, 1,795 successful senior technical leaders were asked what traits were key attributes for success. The obvious attributes of “analytical ” and “innovator” were at the top of the list. What is more interesting is that the least important attribute of all was “Isolated at keyboard”. Why is this? In school, you were graded on your ability to work independently. If you completed all your work and did it well, you got an ‘A’. In industry, the path to success and recognition is less direct. First, you rarely if ever get to work alone. Most jobs are complex and require teams of people to complete the task. Communication and collaboration are a significant part of the work, and Simard and Gilmartin note “collaboration” as one of the top 5 attributes for success. Second, good work is just the start. The work you do may not get recognized because it is either not critical, not visible, or not differentiated from that of others.

Critical work is generally that which directly impacts products and company profits. I spent most of my career in industrial research groups, and in every performance evaluation my ranking was strongly based on the impact I had on products rather than my publication record. Research is important, but transferring that research to products was the key to success. Visibility is another key aspect for success. You need to shine a spotlight on your work and its relevancy. For some, this means presenting the data/analysis/results to others outside of your local group. For others, it might mean working on projects that are naturally in the spotlight because of management interest. Either way, if you work in a vacuum, you will not be recognized. Finally, you need to be able to differentiate your work from that of others. If you are doing the same work that someone with less skills, education, or experience can do, then there is no value to your higher skill set or experience and your reviews will reflect this. I have seen cases where an employee receiving mediocre reviews in one job suddenly blossoms when given the opportunity to work on a task with higher skill requirements. In the end, your success is a function of good work combined with the right projects and tasks that highlight your abilities.

A Company is Only as Good as Your Manager

The person who has the most influence on your career is your manager. Your manager can guide you towards success or push you towards failure. As a friend of mine noted as he was leaving his company in frustration after many years, “… people join companies and leave managers”. To paraphrase Gallup CEO Jim Clifton, nothing can fix a bad manager… not benefits, salary, friends or company culture.

A good manager clearly defines your goals and objectives, values/understands your contributions, promotes your work, and advocates for you. The first three traits of a good manager are reasonably obvious. The last, advocacy, is less so. Many companies have mentorship programs where the mentor guides you through your career trajectory. A mentor takes a passive role in the relationship, offering guidance when asked or needed. An advocate does what mentors do and more. As noted in the paper “Advocacy Vs. Mentoring“, “[a]dvocates stick their neck out. While a lot of mentoring can be done behind the scenes, [advocates] put their name next to your performance and make their support highly visible.” For me personally, the managers who were technically senior to me have also been my best advocates. Not only did they quickly understand and appreciate the work I did, but they also had the seniority in the company and/or the academic community to push for additional opportunities such as putting my name forward to be on a program committee or reassigned tasks to give me the work that I wanted.

Even the best managers cannot work in isolation without feedback from their employees. As much as I hate writing weekly or bi-weekly reports, I have found them to be a helpful communication tool with my manager. If your manager does not know what you did or what you want to do in the future, then they will be unable to effectively advocate for you when it comes to salary, promotions, or new opportunities.

Networking: It’s Not Who You Know, It’s Who Knows You

Networking is one of the best ways to find interesting opportunities whether that be in the same company or a different one. However, unlike the old adage it’s who you know, the reality is more about who knows you and your work. This once again ties into making sure your work is visible both inside and outside the company. If you are known for good work, the network of people that know you and your work from managers within your company to past co-workers and recruiters will reach out to you when a position is available for your skill set. More often than not, my opportunities have come from people who have approached me about available positions rather than the other way around.

The Biggest Risk is Not Taking One

In her book “Lean In”, Sheryl Sandberg talks about her decision to join Google in its early years. She had many offers whose pros and cons she meticulously charted in a spreadsheet and the Google job did not meet her criteria. She pointed this out to Eric Schmidt, the CEO of Google at the time, who told her “[i]f you’re offered a seat on a rocket ship, don’t ask what seat. Just get on.” Eric Schmidt was referring to Google’s growth potential and impact. The same could be said for other jobs or tasks with significant upside along with significant risk. Being engineers, we try to analyze the costs and benefits of each opportunity. We are fully aware of the costs… more work, steep learning curve, potential for failure, etc. However, we cannot fully assess the benefits of opportunities that are outside of our knowledge base and comfort zone. Sometimes we just have to close our eyes and take a leap. Even if the job or task ends in failure, it still holds benefits because you may have developed new skill sets along the way in addition to growing the network of people who know you and your work.

In the past, I tried to take the ‘safe’ route by sticking to tasks and jobs in my technical comfort zone especially when facing work/life balance issues. In some cases, this was the right decision. However, doing this too often meant that my skill set stagnated and this cost me dearly until I rectified the situation. These days, if an opportunity piques my interest, I first say yes before I think too hard about it and scare myself. Afterwards, I figure out how to make things work, whether it be negotiating with my boss about my current workload or negotiating with my family about household responsibilities. My experience has been that for the right opportunity, you will always figure out a way to make it work.

Life is Short… Have Fun

The famous author and poet Maya Angelou once said, “… making a ‘living’ is not the same as ‘making a life’ “. You spend most of your waking life at work. Regardless of how others define success (higher salary, more responsibility, moving up the technical or management ladder, working for a famous company, etc), if you are not happy, then something needs to change. Research shows that you need five things to be happy at work: 1.) Work that challenges you; 2.) A sense of progress or accomplishment; 3.) No fear (of losing your job); 4.) Autonomy; and 5.) Belonging. If your job is not meeting these requirements, then you will not be happy. Many engineers, me included, have left “better jobs” by all objective standards, from tenured faculty positions to coveted industrial research jobs, to do something different. In the end, each person decides what challenges them and provides a sense of accomplishment and independence. In other words, we all define our own metrics for success.

About the author: Dr. Srilatha (Bobbie) Manne has worked in the computer industry for over two decades in both industrial labs and product teams. She is currently a Principal Hardware Architect at Cavium, working on ARM server processors.

Disclaimer: These posts are written by individual contributors to share their thoughts on the Computer Architecture Today blog for the benefit of the community. Any views or opinions represented in this blog are personal, belong solely to the blog author and do not represent those of ACM SIGARCH or its parent organization, ACM.